Threat status

2017 NZ Conservation Status: At Risk – Declining

2015 IUCN Red list of Threatened Species: Least concern

Description

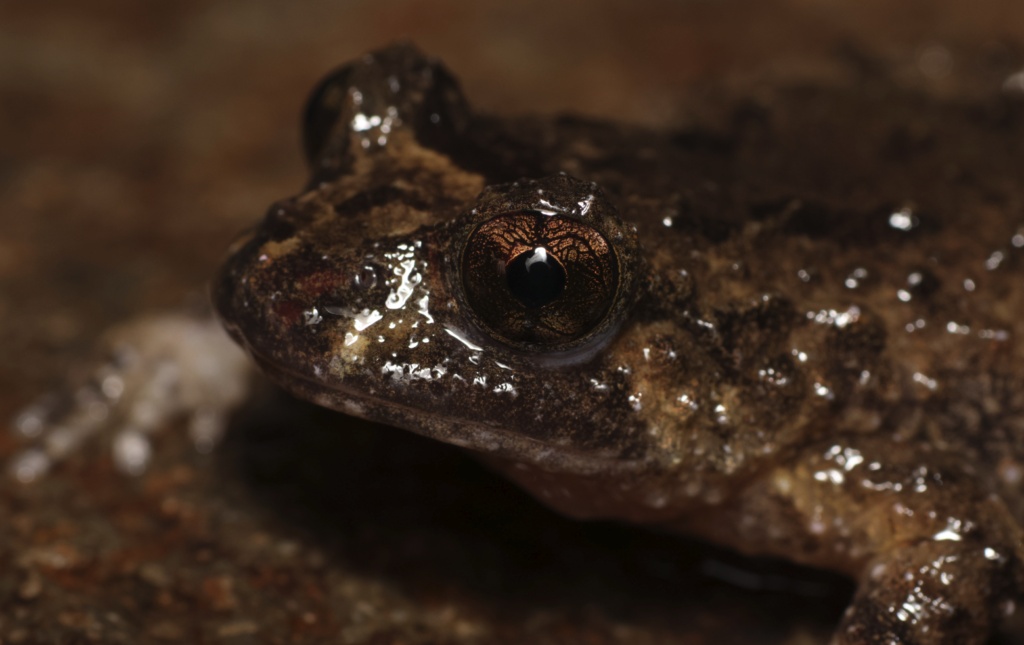

The nocturnal Hochstetter’s frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri) was the first native species of frog discovered by Europeans in New Zealand during the gold rush in the Coromandel. Hochstetter’s frogs are distinct from our two other native frog species and are the most commonly encountered.

These frogs are mostly darker shades of olive green and dark-reddish brown. This colouring allows them to become almost invisible when against moss and the forest floor along stream margins. They have partial webbing between their toes because they are a semi-aquatic species, unlike other native frogs. Hochstetter’s frogs are also far lumpier than our other two native species, they have many little warts and are much slipperier. Hochstetter’s frogs exhibit sexual dimorphism; males have more muscular, robust forelimbs than females. This is another distinctive trait, as the other two Leiopelma species are not sexually dimorphic. Hochstetter’s frogs like all Leiopelma frogs have no tympanum (eardrum) and do not croak like is expected of a “typical” frog.

How big are these frogs?

Frog body size is generally measured as snout to vent length (SVL). SVL is the distance from their snout (tip of their nose) to their vent (bottom). Male Hochstetter’s frogs are the smaller of the two sexes with a SVL <38 mm, females can be slightly larger with SVL<47 mm.

Image by ©Oscar Thomas

Habitat

Hochstetter’s frogs are the only semi-aquatic (lives on land and in the water) of the native species. They are nocturnal and shelter by day in wet crevices or under stones or logs close to the water’s edge in shaded streams. They are the most widely distributed living species of native frog with at least 13 genetically distinct, fragmented and isolated populations across the northern half of the North Island. In some areas, Hochstetter’s frog occurs sympatrically (together) with Archey’s frog (Leiopelma archeyi).

Breeding

Hochstetter’s frog is an aquatic breeder, laying small egg strings between 9-20 eggs. Hochstetter’s frog does not display parental care and they have a tadpole-like larvae stage where the embryos swim, but do not feed, after hatching. Eggs are laid in wet seepages close to the stream, and male frogs do not guard them.

Threats

Introduced Predators

Introduced mammalian predators are a significant threat to all New Zealand native frogs. Increasingly feral pigs are thought to be severely impacting Hochstetter’s frog populations in the coromandel as pig rooting destroys habitat, during which they may incidentally be consumed or squished. It is currently unknown whether wild pigs predate on Hochstetter’s frog or accidentally ingest them when looking for food on along stream margins.

Rats and mice are also believed to be impacting Hochstetter’s frogs. Populations have benefited from predator control efforts in the past. But increased mice numbers after rat control efforts have caused increased juvenile mortality.

Disease

As for all native frogs, chytrid fungus likely poses a low risk to Hochstetter’s frog populations. Chytrid fungus has never been detected in wild Hochstetter’s populations, despite the disease circulating widely in other native and introduced frogs. It is thought Hochstetter’s frogs may be naturally immune to the chytrid fungus. Experimental infection in the lab caused no clinical symptoms and all frogs tested negative for chytrid fungus after 10 weeks.

Habitat Disturbance

Habitat disturbance is a primary and ongoing concern for Hochstetter’s frog. Currently habitat disturbance occurs both directly (e.g. deforestation, gold mining, storm water discharge) or indirectly (e.g. feral goats and pigs causing erosion leading to silt entering streams). Hochstetter’s frogs have been found in exotic pine plantations which often destroys stream health through excessive sedimentation, limiting egg survival. The harvesting of trees occurs every 20-30 years, and likely significantly reduces Hochstetter’s frog population numbers.

Captive Populations

There is a captive population of Hochstetter’s frogs located at Hamilton Zoo, who are working hard to perfect a captive breeding programme.

Fossil Record

New Zealand frogs have an extensive subfossil record. Subfossils of Hochstetter’s frog are abundant and easily identifiable by palaeontologists. Their subfossil record indicates the Hochstetter’s frog have retained most of their historical range across the North Island. However, subfossils exist from the Hawkes Bay and Waitomo. An abundance of subfossils from the Northern West Coast and Nelson area also suggests it was once prevalent in this region.

References

Baber, M., Moulton, H., Smuts‐Kennedy, C., Gemmell, N., & Crossland, M. (2006). Discovery and spatial assessment of a Hochstetter’s frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri) population found in Maungatautari Scenic Reserve, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 33(2), 147-156.

Beauchamp, A. J., Lei, P., & Goddard, K. (2010). Hochstetter’s frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri) egg, mobile larvae and froglet development. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 37(2), 167-174.

Bell BD. (1978). Observations on the Ecology and Reproduction of the New Zealand Leiopelmid Frogs. Herpetologica. 34(4):340–354.

Bishop, P. J., Daglish, L. A., Haigh, A., Marshall, L. J., Tocher, M., & McKenzie, K. L. (2013). Native frog (Leiopelma spp.) recovery plan, 2013-2018. Wellington: Publishing Team, Department of Conservation.

Burns RJ, et al,. (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand amphibians, 2017. Wellington: Publishing Team, Department of Conservation.

Crossland, M. R., Kelly, H., Speed, H. J., Holzapfel, S., & MacKenzie, D. I. (2023). Predator control to protect a native bird (North Island kokako) also benefits Hochstetter’s frog. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(2), A4.

Easton, L. (2018). Taxonomy and genetic management of New Zealand’s Leiopelma frogs (Doctoral dissertation, University of Otago).

Fitzinger LJ. (1861). Eine neue Batrachier-Gattung aus Neu-Seeland. Verhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien. 11:217–220.

Fouquet, A., Green, D. M., Waldman, B., Bowsher, J. H., McBride, K. P., & Gemmell, N. J. (2010). Phylogeography of Leiopelma hochstetteri reveals strong genetic structure and suggests new conservation priorities. Conservation Genetics, 11, 907-919.

Green, D. M. (1988). Cytogenetics of the endemic New Zealand frog, Leiopelma hochstetteri: extraordinary supernumerary chromosome variation and a unique sex-chromosome system. Chromosoma, 97(1), 55-70.

Green, D. M., & Tessier, C. (1990). Distribution and abundance of Hochstetter’s frog, Leiopelma hochstetteri. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 20(3), 261-268.

Longcore, J. E., Pessier, A. P., & Nichols, D. K. (1999). Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis gen. et sp. nov., a chytrid pathogenic to amphibians. Mycologia, 91(2), 219-227

Longson, C. G., Brejaart, R., Baber, M. J., & Babbitt, K. J. (2017). Rapid recovery of a population of the cryptic and evolutionarily distinct Hochstetter’s Frog, Leiopelma hochstetteri, in a pest‐free environment. Ecological Management & Restoration, 18(1), 26-31.

Moreno, V., Aguayo, C. A., & Brunton, D. H. (2011). A survey for the amphibian chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in New Zealand’s endemic Hochstetter’s frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri). New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 38(2), 181-184.

Ohmer, M. E., Herbert, S. M., Speare, R., & Bishop, P. J. (2013). Experimental exposure indicates the amphibian chytrid pathogen poses low risk to New Zealand’s threatened endemic frogs. Animal Conservation, 16(4), 422-429.

Purdie, S. (2022). A naturalist’s guide to the reptiles & amphibians of New Zealand (pp. 152). John Beaufoy Publishing.